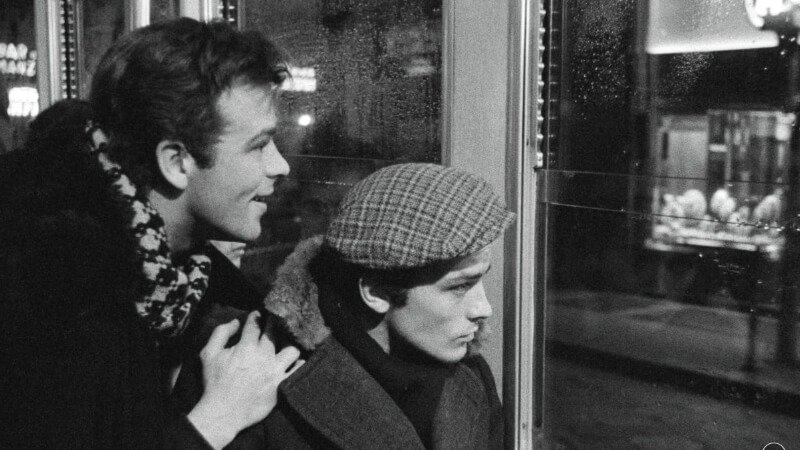

Renato Salvatori and Alain Delon in ‘Rocco and His Brothers’ (1960)

Synopsis

The Parondi family arrives at the Milan train station late at night. It is chilly, and in the long shot of them walking away you notice their modest clothes, the scant belongings they have brought with them. They’re refugees, heading into the darkness, an uncertain future.

It’s Rocco (Alain Delon), his mother, and three brothers. They’d hoped to stay with Rocco’s fourth brother, Vincenzo (Spiros Focás), but they’re turned away by the family of his girlfriend Ginetta (a young Claudia Cardinale). This early, acrimonious encounter introduces the cultural milieu into which the Parondi family is cast. They’re poor farmers from the south. They’ve come north to the proverbial “big city” after the death of the father. It’s their mother’s dream to take advantage of post-war opportunities for a better life. They find an unheated apartment and, in the morning, there’s work possibly to be had shoveling the newly fallen snow.

This is not the Milan of the Duomo, of warm coffee shops and art galleries. Director Luchino Visconti sets much of this gritty, post-war drama in dank, darkened apartments, crowded shops, boisterous bars, and boxing rings.

Each brother has a chapter in the family saga. As they try to find their path forward, each represents a differing viewpoint on the future of post-war Italian society. Vincenzo has already emotionally detached himself from the family, setting his sights on a comfortable life with Ginetta. Simone (Renato Salvatori) is the boozing, womanizing layabout. Ciro (Max Cartier) is the eager, hardworking one, determined to take part in the new economy. Young Luca (Rocco Vidolazzi) is the observer, trying to make sense of where his place will be. And Rocco is the center around which all that happens to the family will revolve.

It’s Simone and Rocco’s relationship that defines the story, proceeding from jealousy to tragedy. As the weight of the brothers’ predicament descends on the family, the various views of how to proceed into the future emerge.

Listen carefully in particular as the mother explains why she made the family move. She felt worn down by their hardscrabble farming existence and oppressed by the neighbor’s condescending attitudes. But that’s her dream, not Rocco’s. He wants only to return to the land, away from city chaos, away from the change that is transforming the new Italy. He’ll sacrifice everything, even his own future, to cling to that ideal and keep his family, even the lost cause Simone, together. Ciro in contrast embraces change, going to school, getting a job at the burgeoning Alfa Romeo plant and making plans to marry.

As we leave the brothers behind, Luca hears out both Rocco and Ciro and he comes to understand them both. He walks off into the bright sunshine, perhaps embracing Ciro’s vision but reminded of Rocco’s burden.

See It

Rocco and His Brothers is at times the proverbial hard watch. Especially for a scene of brutality and rape, but also for the agonizing split between the brothers. We despise Simone’s behavior, and cannot understand Rocco’s. But that’s the intention. Visconti has not set out to tell a pretty story destined for a definitive and happy ending. He’s using the travails of the Parondi family to give Italian viewers a vision of their future, a future where they can find success if only they can discard idealized perceptions of the past.

In Nino Rota’s musical score you can hear precursors of his masterful compositions for another epic about an Italian family a dozen years hence. But unfortunately that tempts comparisons that illuminate some failings. In the second Godfather film, think back to that scene where young Vito joins his friend for a play. Remember how stagey and exaggerated the acting was? Unfortunately, I often felt the same sense of distraction watching Salvatori’s Simone and Delon’s Rocco.

Salvatori in particular just doesn’t have the gravitas and chops needed to inhabit the thuglike Simone. And Delon, in this early starring role, shows only a hint of the iconic cool he’ll come to typify a few years later in Le Samourai. Their showy and overplayed flourishes often took me out of the moment and reminded me I was watching a movie. But then there was Annie Girardot as Nadia, who by turns is vivacious, then sympathetic, then sarcastically bitter; it is the standout performance of the film.

The themes of Rocco and His Brothers are very much a part of their time, and we can’t expect to sympathize with every character’s actions. But I feel it would have had a deep, emotional, and revelatory impact for Italian audiences of the early 1960s. Today, we can appreciate the thematic elements but are left wishing it could have been maybe just a bit more concise and just a bit more authentically acted.