This compelling Japanese crime caper begins, somewhat oddly, with a bunch of male execs of National Shoe company arguing about their latest offering in women’s shoes. Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune), who’s worked his way up during his 30 years with the company, is at odds with his fellow execs. They favor a newer, stylish, but less durable – and thus cheaper – shoe that will sell better and wear out faster. Gondo won’t tolerate sacrificing quality for profits. Though he agrees the leadership has to change, he has his own plan for bringing the company back to prosperity. But as they say … the best laid plans ….

Gondo has put everything he owns up as collateral for a loan to buy a controlling share in the company. As the loan’s approved, he can savor his impending victory for literally only a few minutes. The phone rings. His son has been kidnapped. The caller demands 30 million yen, an unusually extravagant bounty – and a sum he no longer has. Pay up, or the kid dies. But it’s his son. Of course he’ll pay.

Only, it’s not his son. It turns out the kidnapper nabbed the wrong boy, the son of Gondo’s chauffeur. When the kidnapper calls again to acknowledge the mistake, Gondo tells the caller he won’t pay. Of course you will, the kidnapper responds. Can he let an innocent child die? What will it do to his reputation? Gondo insists he won’t acquiesce. His wife pleads with him to pay the ransom. His chauffeur fervently begs him, prostrating himself before his boss. But paying the ransom will ruin him financially and destroy his standing in the company.

What will Gondo do?

See It

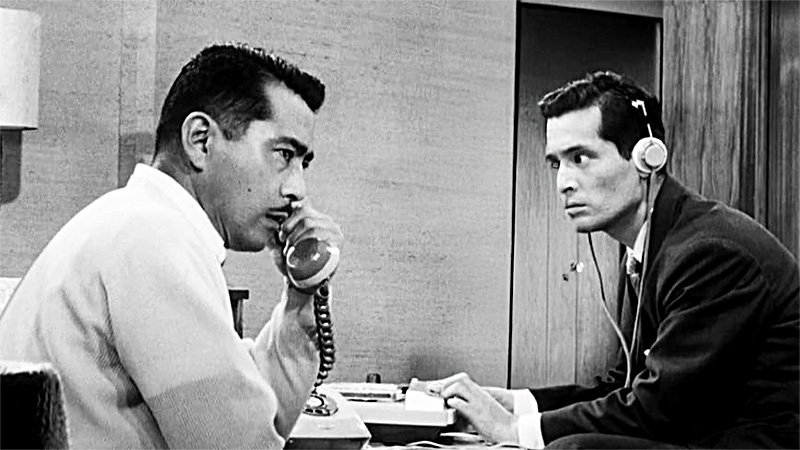

High and Low is two movies. In the first, Mifune is the star. The second is a police procedural in which Inspector Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai) leads a special task force charged with catching the kidnapper and his culprits.

The second half is even more engaging. In an era before cell phones and omnipresent CCTVs, the police show boundless ingenuity and perseverance pursuing a criminal who is clever, methodical, and uncompromising. It will be a half century before they could rig the bags of ransom money with electronic tracking devices; they can only embed chemical packets – one that will release pink smoke if burned and another that will emit a noxious odor if wet. They comb the streets, looking for the areas where the kidnapper would have had the best view of Gondo’s hill-top mansion. They interview vendors. But even after a breakthrough they’re back to square one. Then, a puff of pink smoke (rendered as a single splash of color in this black and white movie) provides a vital clue.

Toshiro Mifune is particularly effective as the hard-bitten exec who has worked his way up from the factory floor to wealth and prestige. Willing to risk losing everything for his son, he’s convincing and commanding as he pivots and contemplates sacrificing someone else’s son on a bet the kidnappers won’t follow through.

Tatsuya Nakadai is his counterpoint: younger, even-tempered, and assured in his role as a police inspector, but still respectful and even sympathetic to the older business exec.

As the investigation leaves Gondo’s grand mansion, perched at the top of a hill and overlooking the city below, we follow the police into the bustling and dirty streets, loud and crowded jazz bars, and darkened passageways teeming with drug addicts. High and Low begins to emerge as a study in contrasts between the haves and the have-nots.

Worthy of special mention is the cinematography. The filming of the scene where the ransom money is shoved through a window as the train speeds by waiting figures on the side of the track is considered a classic. In the city scenes, the camera fluidly follows with as much assurance as in modern epics.

One hesitation? Like many movies of its time, the pace will occasionally seem slow to modern viewers. As the climax unwinds, for example, it becomes a bit tedious as the police track the suspect’s movements; it’s meant to show how careful he is, but it continues long after the point is made.

The tale ends with an unexpected confrontation. It’s reported that director Akira Kurasawa was so impressed by Tsutomu Yamazaki’s hypnotic portrayal of kidnapper Ginjirō Takeuchi that he rewrote the ending especially for him.