Western viewers may need some remedial education to fully appreciate the events and characters that populate Harakiri. That is a word we know as the ritual suicide performed by samurai, a warrior class in feudal Japan. But Harakiri is the act of disemboweling oneself, a word rarely used by used by the Japanese. They more commonly refer to the full ritual of seppuku, of which harakiri is a part. Perched on bended knees, on a square white mat, surrounded by fellow warriors bearing witness, the samurai uses his own sword to slice across his stomach. His “second” waits, sword raised. Once the samurai has completed the cut, and only then, does his second strike off his head to end the ritual.

And now to the story. It’s 1630, in the city of Edo (which would later become Tokyo). Standing at the gates of the Iyi clan’s palace is Tsugumo Hanshirō (Tatsuya Nakadai). Once retained in the service of a disbanded clan, he is now a ronin – a samurai without a master.

Hanshirō has a startling request. He is destitute and wishes to end his life honorably. He asks to enter their courtyard to perform the ritual of seppuku. The clan’s chief counselor, Kageyu Saitō (Rentarō Mikuni), rejects the request. Destitute ronin have been presenting themselves to various clans throughout Edo, hoping for pity and to be given money to go away. The Iyi clan doesn’t want to become a magnet for such dishonorable ronin who have no real intention of ending their lives.

Hanshirō insists he is sincere. Saito asks Hanshirō if he knows Chijiiwa Motome (Akira Ishihama), also of his former clan. No, Hanshirō replies. His master had 12,000 retainers, and it would be impossible to know them all. Saito tells Hanshirō this young samurai, also destitute, had presented himself a few months earlier with the same request, in the same words. Senior Iyi clan members, skeptical of Motome’s intent, insisted on the ritual taking place immediately. They took Motome’s request to return in a few days later as a sign of his insincerity; to preserve the honor of the ritual, they forced him to perform the ceremony, even after learning his sword was made of bamboo. (He had evidently sold the metal blade for money to get by.) The scene of Motome’s death using the flimsy bamboo blade is chilling and excruciating to watch.

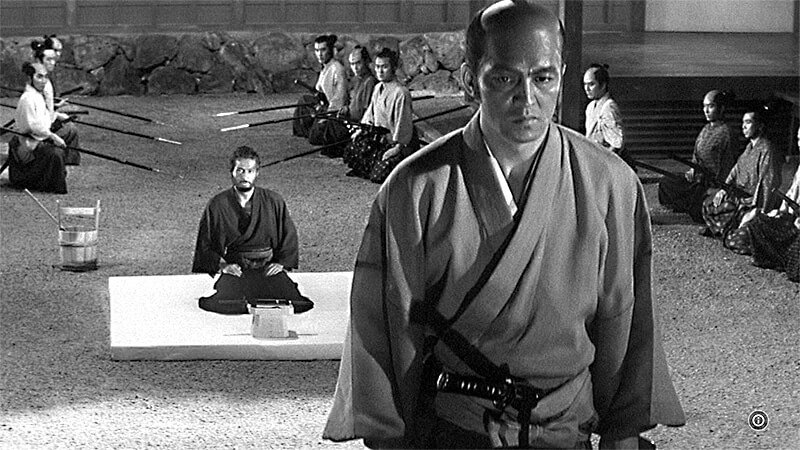

Hanshirō declares he still has every intention of ending his life. And so the ceremony is prepared and, as he is kneeling in preparation, he has one request. He asks for a specific Iyi samurai to serve as his second. Saito is told the man is in his quarters, reportedly unwell. Saitō dispatches a messenger to summon him.

Hanshirō asks if, while they are waiting, he could tell the assembled samurai and retainers his own story as perhaps a cautionary tale. Saitō agrees. And the real story begins to take shape.

See It

Hanshirō’s appearance at the Iyi clan’s palace after Motome’s ordeal is of course no coincidence. Director Masaki Kobayashi intersperses Hanshirō’s account of how his misfortunes led him to that moment with interludes back to the mat where Saitō questions him. A messenger reports Hanshirō’s first choice is too sick to appear. He names another possible second, and then another. All unavailable. All the while his story continues to unfold.

Western viewers probably bring to this story some loose perceptions of samurai tradition, how these fierce and highly skilled swordsmen had pledged to lead a life devoted to honor, to fierce commitment to their masters, to an unswerving code of conduct known as bushido. But Hanshirō’s tale exposes this code of honor as nothing more than a façade erected to maintain the appearance, rather than the reality, of honor. These samurai, enjoying privilege due to their employment, used the “dishonor” of being poor as reason to reject requests and treat their fellows as beggars. In the final moments, as Saitō surveys the ruinous result of his attempts to save face for his clan before the residents of Edo find out the truth, he hits upon a path that is timeless and relevant and recognizable today: a cover-up.

Tatsuya Nakadai’s performance as the aggrieved samurai is finely calibrated to his evolving narrative. He begins telling his story calmly, almost dispassionately, even as the depth of his sorrow and loss grows heavier and sinks in on us. He rises to anger only when his accusations to Saitō fail to bring only convenient equivocation rather than acknowledgement of guilt and an apology.

Most of the publicity stills show Hanshirō in various dramatic sword-fighting poses. Yes, there is some swordplay. But it comes at the end, once the important story has been revealed. A rousing samurai showdown is not what Harakiri is about. It’s is about the hypocrisy of a fading warrior class, so intent on preserving its image that it would sacrifice one of its own.

Western viewers will be tempted to second guess the pace of the movie. Indeed, today’s film editors could make this masterpiece much shorter just by trimming long reaction shots, brooding scenery, and overlong pauses in dialog. But the pace of this tragic tale fits the times and the audience, and it still pulls you along as each new sad fact is revealed.

After experiencing Harakiri, can non-Japanese viewers fully appreciate the cultural resonance of this Japanese tale of vanity, hypocrisy, and betrayal? We should not kid ourselves. But certainly Harakiri dispels many romantic myths about bushido and, by extension, observes that cultural notions of honorable conduct are universally subject to human frailty.