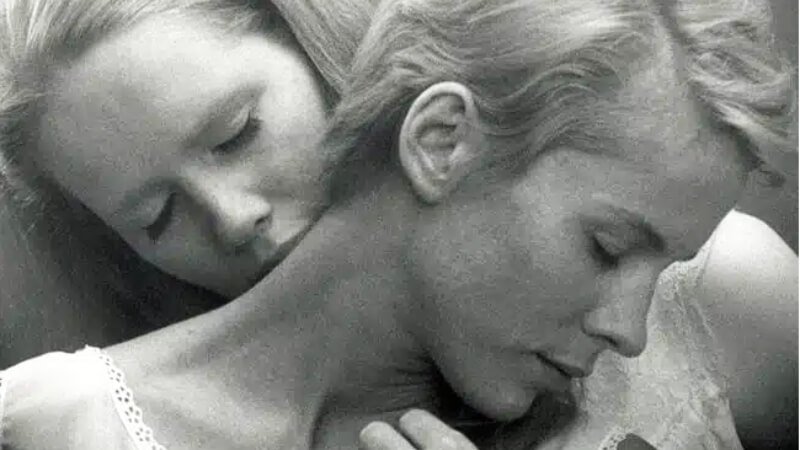

Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson in ‘Persona’ (1960)

Synopsis

You’re best off if, like me, you take in Persona knowing virtually nothing except its reputation as an avant-garde masterpiece. Persona begs to be interrogated on three levels: what’s occurring on the surface, what writer/director Ingmar Bergman tempts you to believe, and what you make of it personally.

On the surface, the “plot” is spare and perhaps intolerably talky if all you want from a movie is an enjoyable few hours of plot-driven entertainment. We begin with a collage of meta imagery, including gut-wrenching scenes of brutality, corpses on hospital gurneys, the famous clip of a self-immolating monk. And a young boy awakening and facing the movie camera, perhaps trying to rub the image into focus.

As we emerge from this teasing cascade of impressions, we learn that famous actor Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) has been hospitalized after what we might call today a psychotic break during a performance. She is perfectly healthy but, as the doctor explains to her nurse, Alma (Bibi Andersson), she refuses to speak. The doctor, feeling she has done all she can, recommends Elisabet recuperate at a seaside cottage, with Sister Alma along to care for her.

During their sojourn, the incessantly chatty Alma tries vainly to induce Elisabet to speak, even a single word. Her attempts range from idle pleasantries to deeply personal and intimate confessions to vitriol and threats. Will Alma succeed in provoking Elisabet to respond?

What is writer/director Bergman tempting us to believe? Certainly he reminds you at the start, middle, and end that you are watching a movie, with scenes of a camera and flickering film. The doctor’s opening preamble is laden with foreshadowing of the action through to the final frame: “I understand why you don’t speak, why you don’t move, why you’ve created a part for yourself out of apathy. I understand. I admire. You should go on with this part until it is played out, until it loses interest for you. Then you can leave it, just as you’ve left your other parts one by one.” Then you can leave. Hang on to that.

Skip It

Perhaps it gives too much away that, though there are two female characters, the title is Persona – singular. Elisabet and Alma look so similar that at times you have trouble discerning who is who. They share common regrets having to do with children, Alma the one she didn’t have and Elisabet the one she did (perhaps that boy in the opening montage). As the emotional climax approaches, we hear the same monologue repeated, first with Elisabet listening, next with Alma delivering. One wonders how Alma knows so much of Elisabet’s sorrows. An unsettling face merges, half of each woman’s visage. And then Elisabet leaves the cottage.

It is a trap to look for definitive answers. Strewn among the scenes are suggestions of intimacy between the two, betrayal, vampirism. Photos from Elisabet’s past, counterweighted by a photo of children being detained by Nazi soldiers. Through to the very end, Bergman strews plot breadcrumbs that I feel he does not intend to lead you to a specific place, but to a place where examination begins. It is impossible to do a plot spoiler for Persona because any fact you reveal has multiple possible interpretations.

What do I make of it personally? One always fears sounding pedantic in making any firm pronouncement about a film that has been the subject of many hundreds of thousands of words of analysis. It ranges from snarky trolls on Rotten Tomatoes (“This film is the artiest of art-house. It can only be described as Mulholland Drive meets Fight Club featuring hot Swedish ladies.”) to deeply probing analysis by the most respected of academics.

And here is my conclusion: I give Persona high marks for artistry, but I don’t recommend it to my movie-loving friends. On the one hand, there is so much I admire. The visually evocative black and white cinematography. Superb and intellectually dense monologues. The emotionally devastating performances by Ullmann and Andersson. The deeply ambiguous themes that can engender endless discussion. On the other hand, there is not much I enjoy.

Me, I enjoy Monet. Dali evokes a smile. Norman Rockwell can bring a melodramatic tear. But when I’m serious, it’s Monet. He inspires. But not from the typical gallery perspective, five feet away, where everything is a swirl of bright, slashing brushstrokes, like the flickering of a camera. You need the right distance and angle, the right lighting. Regardless of my mood, he inspires joy.

By contrast, regardless of distance, lighting, or angle, I get nothing from another artist wish slashing strokes, Jackson Pollock. He leaves me cold; nothing resonates. And that’s how Persona affected me. I admire the technique. But emotionally it leaves me cold. I know that, if I stepped up close and concentrated, I could lose myself for hours, days, excavating ideas, patching together out of the chaos of his images what might even be one plausible explication out of dozens that Bergman tempts us to believe. But for me, the effort is not worth the potential reward. Persona is an entirely personal experience for each of us, and mine lacked warmth and joy. Your experience will be different.